Language is a fascinating and complicated tool for gender expression, as well as communication.

I'm so excited to share this collaboration with Lily, a Japanese language teacher (who I first met when we were both teenagers)!

We discuss how to express femininity, masculinity, how these are intertwined with politeness, and LGBTQ+ identities and inclusion in Japan.

Let's dig in!

Rey: Hi Lily, thanks so much for joining me here on Amplify Respect! I am really excited to ask you about how people express gender in the Japanese language. Lily, can you please share a bit about your experience with learning Japanese, teaching Japanese to English speakers, and your services to help people traveling to Japan?

Lily: Hi Rey! I’ve really enjoyed discovering your work and getting back in touch after so many years. I feel I’ve learned a lot from your posts since I started following (around this time in 2023 I think?), and they’ve given me a lot of food for thought as well! I got into learning and later teaching Japanese through a combination of family history and circumstance.

Both sets of my great-grandparents on my mother’s side immigrated to the US from Japan sometime around the turn of the 20th century, and so my maternal grandparents (Miyo and Frank) spoke both Japanese and English; but my mother and her sister were brought up with English only. My parents were enthusiastic about giving me exposure to Japanese language and culture when I was growing up.

I started studying Japanese language much more seriously in my teens after a number of my friends and I got really, really into reading comics from Japan that had been published here in English, a few of those friends started studying Japanese themselves, and, in peeping at their classwork, I started realizing how much I really didn’t know. That was around 2006, and we haven’t stopped studying since! In fact, one of those friends is currently living and working in Japan.

I started tutoring Japanese part time around when I started college, when I realized I could make money talking about this increasingly intense interest. I feel obligated to say for any considering it that self-employed educator is certainly not one of the most financially stable jobs out there, but it is a lot of fun.

I strongly believe that learning a second (or third) language (any language, not just Japanese) – and really gaining an understanding of it and finding personal connections to the culture – is a highly undervalued experience.

It can lead to entirely new ways of thinking and contribute to other skills like creativity and problem-solving, and be a path to gaining real insight into another part of the globe and how people there live and think and see the world.

I do travel consulting and tour guide services for a similar reason to why I teach – I love telling people about things! And I also love traveling.

(Check out Lily's classes, posts, art prints, and language resources here: https://ko-fi.com/lilycernak)

Rey: Men and women tend to speak a bit differently in Japanese, right? Can you describe the difference? If someone speaks in a "gender non-conforming" way, how can that be perceived by others?

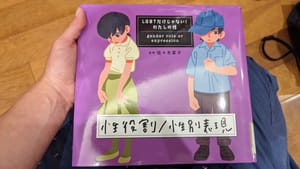

Lily: That is true. I’ve struggled with the clearest way of teaching this topic for some time. I think there are two concepts that are very useful for conceptualizing how gendered language exists in Japanese: “Japanese as LEGO pieces” and a “politeness spectrum” of the language. By “Japanese as LEGO pieces,” I mean that Japanese can be very modular. While things like verbs and adjectives themselves do get conjugated (a word itself changing form to reflect tense, etc) there are also a lot of other small pieces that can be tacked on to sentences to additionally change grammar, or to affect the emotional tone of a sentence.

And some of these small pieces, especially in casual-style Japanese (what you might speak with family and close friends and also is used a lot in things like song lyrics and narrative writing) may be selected at least partially based on how one wants to express oneself in terms of gender. This brings us to the second thing: When I started constructing lessons to talk about gendered language in Japanese, I started by making a “spectrum of gender” diagram for some of these modular language components before realizing that describing some of them as specifically “feminine” and some of them as specifically “masculine” felt too limited.

A cisgender woman, for example, might use “masculine” language components as well as “feminine” ones, and/or ones in the middle of this “spectrum of gender.” Which ones she would choose to use might depend on many factors – her age, her personality, her mood, who she is talking to, where she lives or grew up, what type of setting she happens to be speaking in at that moment, how she wants to be perceived by who she is talking to… and so on and so forth!

For LGBTQ+ folks, particularly those who are transgender, the language components they choose to use or not use in a given conversation may also be affected by whether they have or have not come out to everyone in their lives. So I decided to change my approach and to present gendered language in Japanese in terms of a “politeness spectrum” rather than a “gender spectrum.” Generally speaking, speech that skews “ruder” or maybe “brusque-er” can also tend to come off as more “masculine” in Japanese, and speech that skews “politer” can tend to come off as more “feminine.” Humans have sure made language and its intersection with ideas of social norms complicated, haven’t they!! I’d like to note here that there are some excellent articles and podcasts on first-person pronouns and LGBTQ+ life in Japan from the website Tofugu which note that the Japanese language may actually be gradually becoming less gendered over time.

(Check out "Beyond the Binary: A Queer Take on Gendered Japanese" written by Cameron Lombardo on Tofugu: https://www.tofugu.com/japanese/queer-japanese/)

I don’t have any concrete evidence of my own on this, but anecdotally I think they may be right. If we revisit this topic in a decade or two, it may be the case that my idea of a “politeness spectrum” as it relates to “masculine-skewing” or “feminine-skewing” language components may be very outdated! In terms of perception by others: I could imagine both situations where significant deviation from what someone might expect based on your perceived gender is seen as just a quirk of personality, and also cases where it might lead the person you are speaking to to realize they had misread your gender identity.

There are a number of scenes in popular media (my reference points are largely from anime, but I am sure there are examples in novels and film as well) where a character’s intention is to be perceived as a specific gender (either because they are transgender, or for other reasons to do with the plot of the story), and whether they do or do not consciously adjust their style of speaking often features into the storytelling.

That being said, in many cases in fiction the effect of the character’s speech style may be played up for drama, and in real life I could also definitely imagine cases where the person you are speaking to doesn’t particularly notice your style of speech!

Rey: What do you think are the most gendered aspects of speaking Japanese, or what comes up most often with your students in terms of gendered language? Does gender come up when speaking about oneself, and/or when describing other people?

Lily: The first thing that I usually bring up related to gendered language in Japanese is first-person pronouns, partially because I find this topic fascinating and partially because it’s something students can listen for as soon as they learn about it if they watch anime or Japanese movies.

Japanese has an array of first-person pronoun options, and while there are elements of gender attached to all of them to some degree, I think they can also be thought of along the lines of that “politeness spectrum” I mentioned earlier.

For example, “watashi” (私) is towards the polite end of the spectrum, and so can sound more feminine-skewing if the situation it is used in is casual, but in a formal work situation may be the most appropriate choice regardless of gender. Many people swap which first-person pronoun they are using as their social surroundings shift throughout the day (or even moment to moment – maybe someone is “watashi” while speaking to their boss, but then leaves the meeting and texts their friend to complain about the meeting, using a completely different first-person pronoun). Part of what I find so interesting about first-person pronouns in Japanese is what to do about translating them. It can be very difficult to indicate, especially when writing a translation for an audio dub rather than translating something that will just be in print, that someone is using an unexpected first-person pronoun, or that they are switching between two different pronouns.

I was watching an anime recently where they simply didn’t translate a switch in pronoun at all – even though it was important to the plot (the anime is set in a fantasy world, and the character was viewing someone else’s memories, so when they snapped back into their own mind they initially spoke with the other person’s first-person pronoun rather than what they would usually use themselves, and their companions reacted with mild confusion).

And, going in the other direction, when English media (whether that be news clips, movies, or comic books) is translated into Japanese, first-person pronouns must be chosen for anyone who is speaking a significant amount in that media.

It’s fascinating to see what first-person pronouns translators choose. For example, Tom Holland’s Spider-Man uses boku (僕, polite-ish but a bit further towards the “masculine-skewing” side of the spectrum than watashi), at least some of the time – I haven’t watched a full Spider-Man film dubbed into Japanese (yet!).

These are some of the experiences that I think make starting to learn about another language or another part of the world so rewarding and exciting. It can take a while to begin seeing those rewards, and it can be quite confusing or overwhelming at times! But if you take it step by step and keep at it, over time there are so many opportunities to see the world through a new lens or from a new angle. If you’d like to read more about this topic in particular or about LGBTQ+ life and culture in Japan, I highly recommend the Tofugu articles and podcasts! They’re all available for free.

(Check out "Coming Out In Japan" written by Cameron Lombardo on Tofugu: https://www.tofugu.com/japan/lgbtq-identities/)

Rey: What kinds of questions about gendered language often come up in your language lessons?

Lily: Actually, I think I’m often the first one to bring up gendered language as a topic in my classes! Beginner and even intermediate Japanese textbooks don’t tend to emphasize gendered language much, which is understandable in that they are often trying to give example sentences that are very generally usable and don’t have a lot of those “modular” elements to them that are more personal.

This is one of many reasons why I think if you are studying a language it’s important to use a textbook for structure, but watch movies and YouTube videos and things for a sense of how the language might sound outside of the textbook. Rey: How possible is it to talk about someone in a gender-neutral way in Japanese? Is there an equivalent of using "they" and "them" instead of "he" or "she"? (The equivalent of "That person, they went to the store to pick up their lunch." or something like that?) Lily: It is very possible! It is actually significantly easier to speak about someone in the third person without specifying gender in Japanese than in English.

It would not sound odd at all in Japanese, in fact, to more or less never use overtly gendered language like “she” or “he” to refer to a person. This is due to a few factors.

One is that, both in formal and casual Japanese, words that are not considered necessary in context (which often includes pronouns of all types, first-person, second-person, and third-person) are frequently omitted from sentences.

Another is that in place of formal prefixes like “Ms.” and “Mr.,” formal Japanese uses the suffix “san” which is gender neutral.

The third is that even when words are not being omitted, it is common practice to use an individual’s name in place of pronouns like “she” or “he” (especially if speaking somewhat formally, since using someone’s name – especially if it is their surname + “san” – rather than a pronoun sounds less familiar). For example, an exchange in English which might go “Where is Ms. Miyagawa? Did she leave already?” “Yes, she did” might in Japanese be phrased roughly, “Where is Miyagawa-san? Already left?” “Yes, left.” Occasionally, the non-necessity for pronouns in Japanese can cause some significant indecision for English translators and localizers, who when given a segment of Japanese without sufficient context (say, for example, an excerpt of audio from a video game or text from a novel where the full product is not yet available, or a character whose gender identity and/or preferred pronouns are unclear) may be left uncertain as to what pronouns to use in English to refer to the persons mentioned!

Rey: What words can you use to describe someone as trans or non-binary in Japanese? Are these words considered respectful?

Lily: This is a topic I must admit to not being very knowledgeable about! Japanese tends to borrow a lot of words from English, especially words being widely circulated in American media, and I’ve seen トランスジェンダー (toransujendaa, “transgender”) and ノンバイナリー (nonbainarii, “non-binary”) used in places online like major newspapers and LGBTQ+ info sites. As far as I know, both words are considered similarly to in English (general terms, not disrespectful).

I am a somewhat introverted person and when traveling sometimes see a lot of sights without making the acquaintance (at least on a more personal level) of many new people! And so far happen to not have met many folks in the LGBTQ+ community in Japan.

I love learning new pieces of language, though, and am hoping to expand this part of my vocabulary in the future! If anyone reading this has experience with other words related to transgender or non-binary folks in Japanese, please comment and share!!

—

Lastly – I wanted to share a photo that a friend took this year at Tokyo Pride this year! I really like it. It’s a consultation booth for wedding services for gay couples, and they did some really cute wordplay with their banner.

The words for “wedding” (結婚 kekkon), “like/love” (好き suki) and “start/begin” (始まる hajimaru) all happen to contain a component that on its own means “woman” (女) but for this sign they replaced all of those components with the one that means “man” (男).

Japan LOVES wordplay (as do I!), and I think it’s also a fun way for the booth to demonstrate a more open-minded outlook on traditional ideas of love and marriage.

Rey: Thanks so much, Lily, for sharing your time and expertise with us! This is amazing and helpful info that I will treasure as I continue to study Japanese.

If you found this article helpful, please contribute to Lily's tip jar here: https://ko-fi.com/lilycernak

(And please check out Lily's classes, posts, art prints, and language resources here: https://ko-fi.com/lilycernak)

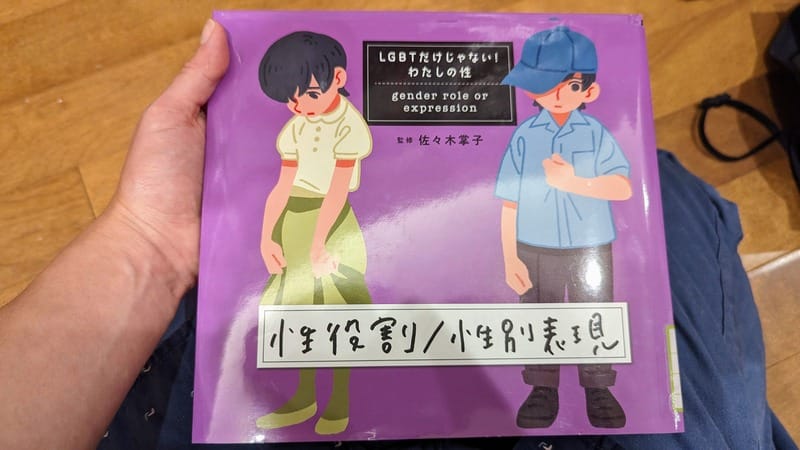

If you're interested in reading more about Japanese culture and travel, check out this article about my experience traveling in Japan and visiting a gender studies library:

Please let us know what you think in the comments!